Development Bargains in Action: Kickstarting Good Job Creation in Rwanda’s Outsourcing Sector

by Kartik Akileswaran, Ben Hyman, and Jonathan Mazumdar

Rwanda’s remarkable success seen through its bet on growth and development

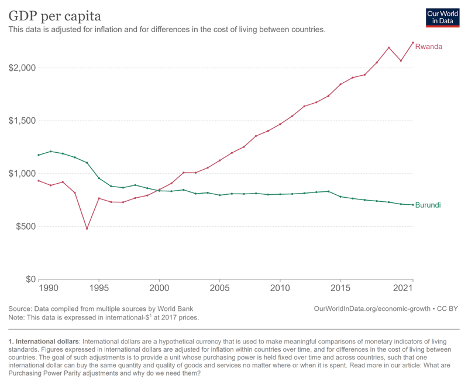

Rwanda’s remarkable development journey over the last three decades is well documented. What is so uncommon about Rwanda’s transformation is that it came in the aftermath of a devastating genocide. Of the seven Sub-Saharan African countries to experience a conflict in the 1990s and early 2000s most saw their economies permanently damaged; only Rwanda and Ethiopia have since seen their economies outperform peer countries that avoided war. Comparing its growth trajectory with Burundi (see chart below) – a neighboring country of similar size, colonial experience and ethnic divisions, that also experienced a civil war in the 1990s – highlights the scale of Rwanda’s progress thus far. Rwanda’s growth has enabled sharp reductions in poverty and rapid gains in wellbeing; the share of population living on less than $2.15 (2017 PPP) per day dropped from 75% in 2000 to 52% in 2016, and under-5 mortality declined to nearly half the average rate for Sub-Saharan Africa in 2021.

A real (development) bargain

An essential component of success, without which this sustained growth episode would have not been possible, has been the genuine commitment of Rwanda’s elites to achieve economic transformation. Rather than focusing solely on redistributing fixed wealth, leaders across government, business, and society have adopted a mentality of growing the pie.

Researchers refer to the tacit agreement among the political elite in a country as a “political settlement” or “elite bargain”, and in many cases, the outcome is one that favors self-enrichment for personal interest groups as opposed to widespread growth and development. Oxford professor Stefan Dercon calls the particular choice to pursue growth and development, made in Rwanda and other places, a “development bargain”. Development bargains are crucial because in most low-income countries a small elite tends to control the government, much of the wealth, and sometimes even the social norms – making their support essential to achieving growth.

Experiences from countries across Africa, including Rwanda’s neighbors, highlight that such bargains often do not materialize, or that even when they do they fail to persist. Three main reasons help explain how Rwandan elites have coalesced around a development bargain – there were few established interests opposing it, the new government needed to build unity, and important figures chose to do right by their country.

Weak vested interests: The sheer scale of the rebuilding project after 1994 meant that there were few people with a vested interest in the economic status quo and almost everyone had something to gain from growth and good governance. Additionally, the conflict was ended by a military victory rather than a negotiated settlement, avoiding the need to tie-up the state’s scarce resources in order to buy off all the necessary constituencies to secure peace.

Unifying vision: The new government knew that a return to conflict was a real possibility and they wanted to avoid it at all costs. Development offered a shared goal to unify the nation and heal divisions. What’s more, a commitment to inclusive, stable, and impartial governance was necessary to win public confidence and prove that this was a truly national government.

Leadership: Finally, the actions of a few key individuals were pivotal. In the aftermath of ethnic conflict in many countries, the new ruling elite seeks to cash-in on power while they have the chance, slowing the recovery and increasing the risk of relapse. Rwanda’s more favorable trajectory was shaped by the personal decisions of those in power after 1994.

The process of change

Rwanda’s success has not just been about a development bargain, it has also been about actually getting things done. The practical challenge of effective policy implementation was immense. When the government resumed business in July 1994, the civil service had been hollowed out by the conflict; for instance, only seven people reported to work at the Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning (MINECOFIN).

Precisely because of limited state capability, prioritization and focus were critical to get started and to make consistent progress. One way this was pursued was through top-down focus on accountability and performance. For example, leaders have worked hard to instill norms of accountability and transparency across government. This is best exemplified by the Imihigo system of performance contracts for all levels of government, which cascades from ministries down to all civil servants. In parallel, the annual Umushyikirano event, or national dialogue, provides an opportunity for citizens to directly engage their leaders, review results against targets, and provide input into decisions. It is no surprise then that surveys of experts report that most ministries regularly deliver on their mandate and that the government is significantly more effective than its peers.

At the same time, Rwanda’s development strategy has encouraged the emergence of pockets of effectiveness in key areas of the bureaucracy. Rather than embarking on an abstract state-building project, the government has succeeded by developing capabilities in the context of specific needs in the country.

For example, once the basic functions had been rebuilt, MINECOFIN was handed wide-ranging powers to control planning and donor management alongside its more traditional role as a finance ministry. There were also management reforms, which have involved hiring many talented young graduates from the diaspora, giving them significant responsibility, and promoting based on merit. As such, it has developed into an effective body that plays a crucial co-ordinating role within government. In recent years, the evolution of capabilities has led to greater policy experimentation, including exploring unconventional opportunities for resource mobilization such as bilateral peacekeeping missions and refugee resettlement.

Other such pockets of effectiveness have emerged in important areas. Building on lessons learnt from past responses to public health threats, the Rwanda Biomedical Centre (RBC), the national health implementation agency, played a decisive role in the rapid and effective containment of Covid-19. And as elaborated in the next section, the Rwanda Development Board (RDB) has developed into a powerful and effective promoter of private-sector-led economic growth, which is key to the nation’s next phase of development.

What development bargains can enable: the case of global business services as an emerging sector in Rwanda

At the same time that Rwanda has progressed immensely in its development journey since the 1990s, the country’s ambitions remain high for the coming years. The country’s national development strategy envisions becoming an upper-middle-income country by 2035 and a high-income country (HIC) by 2050 (respectively ~4x and ~12x growth in GDP per capita from 2022). To make progress toward these ambitions, key economic challenges will need to be addressed.

For instance, Rwanda has 4 million youth (age 18-35), 27% of whom are unemployed and an additional 31% of whom are underemployed. Entry-level wages are very low, often only ~$100/month, and average income is even lower (GDP per capita was $966 in 2022). The country needs to diversify into higher-productivity economic sectors and create tens of thousands of good jobs to enable workers to be more productive and achieve higher living standards.

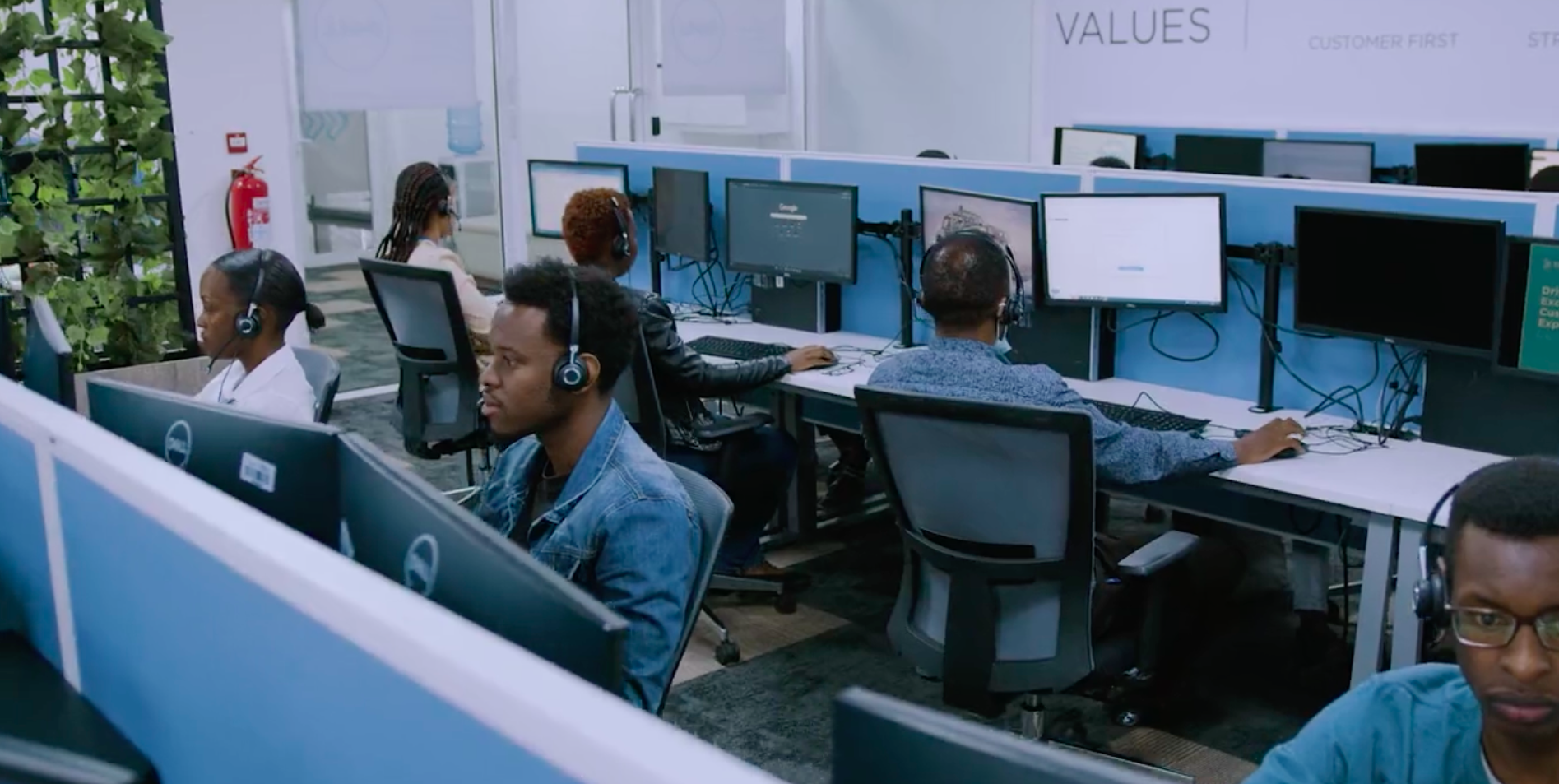

Being a small, landlocked country with high transport costs and constrained access to markets means that the traditional export-led, manufacturing-based economic strategy may not be as straightforward for Rwanda to pull off as it was historically for other countries. Well aware of this reality, the government has for years emphasized IT-enabled services as a high-potential area that skirts these constraints. Global business services (GBS) is one such sector, including activities like customer support call centers and IT outsourcing (e.g. IT support, software testing, data labeling,and basic coding). GBS is a sector that other developing countries have excelled in – such as India and the Philippines – and has provided a pathway to entering even higher-productivity services.

Until recently, the potential for GBS in Rwanda was not much more than a promising idea. While outsourcing had been mentioned in various studies and government strategies (dating back more than a decade), the country faced the typical cold start problem of entering into a globally-competitive sector with no existing base of firms and industry know-how. Forward-thinking leaders within the Government of Rwanda needed to tackle the substantial challenge of promoting investment into the sector and removing key barriers that discourage new investors and hinder growth. Over the past 18 months, a core team at the Rwanda Development Board (RDB), together with Growth Teams, has embarked on exactly this process.

A first step was to translate the strategic thinking – identifying GBS as a priority sector – into tangible actions to be taken. Given the sector is dominated by global players that maintain customer relationships and offshore operations to lower-cost sourcing destinations, this consisted of developing an investment case to attract anchor firms to Rwanda. The RDB team researched the country’s competitiveness in the sector, comparing the costs of key inputs across alternative sourcing countries and collecting missing data to strengthen the case – e.g. by mapping the available talent with requisite language skills, which is a key factor for sector growth. The result was a compelling articulation for why a GBS firm might consider setting up in Rwanda.

Next up was to actually get in touch with potential investors, listen to their needs, and adapt the investment case accordingly. Large information asymmetries persist across borders, and global firms are often unfamiliar with the on-the-ground reality in Rwanda. A strong investment case is simply a tool for engaging with private firms. The true test comes from their response. The team at RDB identified criteria to filter the universe of GBS firms to those with likely interest in Rwanda, built an investor pipeline of 80+ prospective investors using that criteria, initiated outreach to those investors, and facilitated country visits for interested players.

These efforts are beginning to yield results. Over the last 18 months, a number of outsourcing companies have launched operations in Rwanda, including leading players such as TekExperts (launched end 2021), CCI Global (launched end 2022), and a range of smaller software development firms. Today, over 15 GBS firms, employing roughly 1,500 Rwandans in good formal jobs, are providing a range of business process outsourcing (BPO) and IT outsourcing (ITO) services to global markets. The 1,500 seats created thus far are quality jobs paying $200-400 per month for entry-level positions – 2-4 times more than the prevailing wages from local employment – and up to $1500 per month for higher-skilled roles. These market signals provide validation that Rwanda does indeed offer a compelling value proposition in the GBS sector.

However, the job is not done. Where there are barriers in the economy that hinder further investment and growth – e.g. a limited labor pool with adequate language skills – the government will need to figure out how to unlock those constraints. Key to this process is the active exchange of information between government and firms in the sector to identify these constraints, try out remedies, and gather feedback on actions taken. The RDB team is already engaging in exactly this public-private collaboration. For example, a recent regulation on working hours, introduced by another part of government, has created concerns for GBS firms that need to provide 24/7 service for clients (typically through overlapping shift windows aligned to foreign time zones). Here, the team is driving intra-government coordination with the relevant ministries to identify and implement a resolution to this issue.

The emergence of the GBS sector in Rwanda illustrates the possibilities that result from the marriage of a development bargain and effective government action to promote growth. A unifying vision set a clear direction for the country, within which knowledge-based services were identified as an engine of economic transformation. Strong leadership at various levels in the system created opportunities for investment and growth. And weak vested interests, particularly in a nascent sector like GBS, allowed government and firms to build a new coalition for progress in a productive, job-creating part of the economy.

Looking ahead, RDB remains at the forefront of enabling continued growth, diversification, and job creation. Working side-by-side with Growth Teams, RDB has attracted two new global GBS firms to set up operations in Rwanda this year itself (with several more expected soon), helping to create 6,000 good jobs in the GBS sector by 2025. These jobs will provide a path to improved living standards and enable young Rwandans to further invest in their wellbeing. Importantly, RDB now has deeper experience with the problem solving process that lies at the heart of accelerating economic growth, and can apply those capabilities to unlock new economic opportunities that benefit all Rwandans.

Ben Hyman is Growth Associate at Leta, an AI-driven tech provider for logistics in Africa. Views expressed here are his own and do not represent those of his employer, Leta.